In the fourth quarter of the 19th century, as the dust had settled from the Civil War and end of many long years of border skirmishes known to history as ‘Bleeding Kansas,’ the state of Kansas experienced a renewal.

War veterans, industrious prospectors, and those who wanted to make a name for themselves in America’s wilder regions moved west of the Mississippi in huge numbers, transported via the Union Pacific Railroad. These brave and hearty folk started towns and settlements all along the lines of the Union Pacific and beyond, one of which, in the winter of 1878, was Garden City.

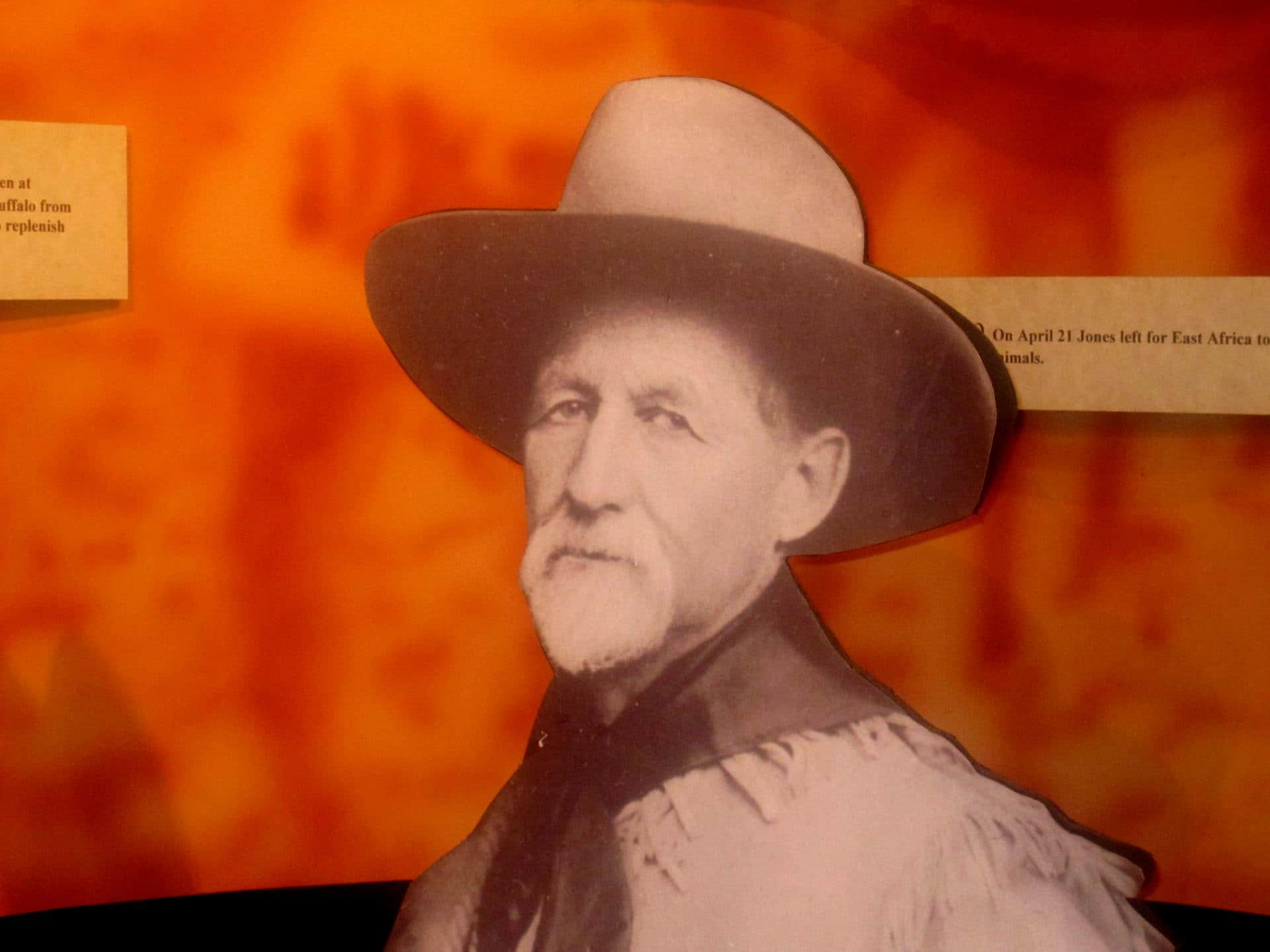

A bit more than a decade earlier, a young man of 21 named Charles Jesse Jones dropped out of Wesleyan University. He was the second of twelve children, an animal lover, and fostered a longing for adventure. He married, and moved with his new wife to Troy, Kansas, not far from the Missouri border to plant orange trees.

Charles’s craving for adventure soon outgrew his orchards, and he took up what was THE flourishing business of the age, and became, like so many adventurers of the age, a buffalo hunter.

He became successful after only a few years. So successful, in fact, that he earned the nickname he would carry with him for his whole life: Buffalo Jones. It was during this time that he bragged ‘I have killed more buffaloes than any man ever did.’

While this claim proved difficult to verify, it was enough to cause the founders of Garden City to invite Buffalo Jones to assist in the promotion and prospecting of their new town. By this point, Buffalo Jones was tired of hunting buffalo, the value of the beasts were plummeting and, perhaps, he had an inkling that the trade, as it was, couldn’t subsist much longer.

In any case, Buffalo Jones settled on 160 acres of ranch land in what is now Finney County, and worked with the founders of Garden City in convincing not one but two railroads, the Atchison-Topeka and the Santa Fe, to make stops in Garden City.

For his work in helping to build and populate the city, Jones was named Garden City’s first mayor.

From Hunter to Breeder

In many areas of the Western plains, cattle had replaced the once unimaginable herds of bison. Overhunting and encroachment by humans into buffalo territory had pushed the animal with both hands to the brink of extinction.

The winter of 1886 proved however, that the cattle, strong as they might be, were no match for the natural sturdiness of the buffalo, and in blizzards and torrents of snow that rose to chest high, ranchers saw their entire stock lost.

Remembering the resiliency of the animal he’d hunted with such vigor, Buffalo Jones had an idea: he would crossbreed the cattle that had been so unequipped to handle the harsh winter with the buffalo, which handled it so well. He called his new crossbreed the Cattalo.

In addition to enhancing the stock on the plains, Jones also saw this as a way to aid the survival of the species he once hunted, and in who’s plight he felt a certain level of responsibility.

To accomplish the feat of bioengineering known as the Cattalo, Mr. Jones needed to obtain some buffalo.

He gathered the few he could find left roaming the plains, and sent letters and telegrams to ranchers he thought might have a few on hand. He traveled as far as Canada in his pursuit of what was once spread across the plains in every direction.

By the end of 1888, he had collected some 150 buffalo, which represented, according to one account, ‘half the existing population.’

While his plan to market Cattalo failed due to the species’ inability to reproduce, Jones found a new mission, replenishing the American buffalo.

First, he was granted breeding land in New Mexico, where he sought to continue to grow his herd. Then, he was charged by US President Teddy Roosevelt with the preservation of America’s last wild buffalo herd, as few as 30 animals in Yellowstone park.

Jones went to Yellowstone as it’s first official game warden. He brought with him three breeding bulls, and, the next year, the superintendent of America’s first National Park reported to Washington that, under Jones’s deft leadership, the Yellowstone herd was flourishing.

While he only held the position for 5 years, he left on good terms, knowing that the buffalo herd was growing strongly, and convinced of the fact that the American buffalo would persist in the west.